THE HISTORY OF UPCYCLING

Upcycling, the process of creatively transforming waste materials or unwanted items into new, higher-value products, is not a modern phenomenon. Its roots stretch far back into human history, intertwining with cultural, economic, and environmental dynamics. This article explores the evolution of upcycling, from its humble beginnings to its current status as a global sustainability movement.

The Origins of Upcycling: Necessity and Resourcefulness

Before industrialization, upcycling was primarily driven by necessity. People repurposed materials to extend their utility in a world where resources were limited and production systems were labor-intensive.

Prehistoric Practices

Early humans utilized every part of natural resources, such as animal hides for clothing, bones for tools, and sinew for binding.

Creativity often stemmed from survival needs, leading to innovative uses of available materials. For example, broken tools were reshaped into new implements.

Ancient Civilizations

In ancient Egypt, worn-out papyrus scrolls were repurposed for secondary uses.

The Greeks and Romans recycled metal and glass to create new items due to the scarcity and high value of such materials.

Textiles were upcycled extensively. In medieval Europe, clothing was patched, repaired, and handed down, eventually becoming rags for papermaking.

Rural and Artisan Recyclers

Many lesser-known but highly skilled artisans also played a role in recycling materials. Traditional rural dressmakers across Europe, such as in Scandinavia or Eastern Europe, integrated patchwork and quilting techniques into wearable garments. These practices influenced Victorian and Edwardian fashion trends in embellishment and repair.

Women of the Court

Women in royal courts and aristocratic circles often commissioned designers to refashion their garments. The Duchess of Devonshire, for instance, was known for reusing rich materials from older gowns, as was Empress Eugénie of France, who admired incorporating historical elements into her wardrobe.

The ethos of recycling in fashion during these centuries reflects both the practical limitations of materials and the creative ingenuity of designers. For these figures, upcycling was not just a necessity but also an art form, blending sustainability with high aesthetics.

Cultural Innovations

Indigenous communities worldwide practiced upcycling, often out of reverence for natural resources. For instance, Native American tribes creatively reused buffalo remains.

Japanese culture developed the concept of mottainai, an ethos of avoiding waste, which inspired techniques like boro stitching—patching and quilting old fabrics into durable garments, and Kintsugi, for lifestyle objects aims to beautify broken ceramics.

Image Source:Vintage mottainai Japanese jacket on kimonoboy.com

The Industrial Revolution: Decline and Revival

The Industrial Revolution (18th–19th centuries) marked a turning point in production and consumption. While mass production initially reduced the emphasis on repurposing, economic and wartime pressures rekindled the practice.

Regency and Empire Designers

In the early 19th century during the Regency and Empire periods, simpler, column-like silhouettes emerged. Seamstresses often repurposed older, heavily embroidered 18th-century gowns into these new styles by cutting away ornate embellishments and using them as appliques or trims on lighter, muslin-based designs.

French Couturiers and Dressmakers

French dressmakers, particularly in the 19th century, were celebrated for their ability to transform existing garments. Designers catering to aristocracy often refashioned gowns to keep up with evolving styles. Many Parisian ateliers used lace, beading, and fabrics from heirloom garments to create new pieces, preserving the historical and sentimental value of the materials.

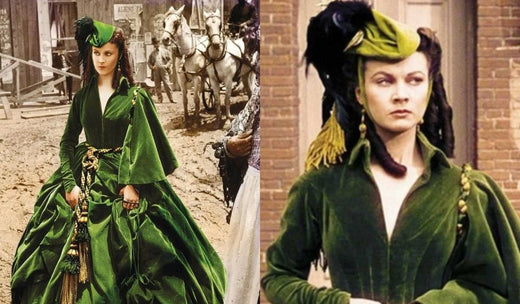

Victorian Couture Recycling by Charles Frederick Worth

During the Victorian era, the practice of upcycling found its way into the world of haute couture through designers like Charles Worth, who is often referred to as the “father of haute couture.” Worth’s designs, renowned for their opulence and craftsmanship, often featured elements of material reuse. In a time when fabrics like silk, velvet, and lace were costly and labour-intensive to produce, Worth skilfully incorporated vintage textiles and embellishments into his creations. This was not merely a pragmatic choice but also a stylistic one, as antique fabrics lent an air of timeless elegance to his designs. Victorian society’s focus on grandeur and sophistication made such practices fashionable, and Worth’s innovative approach influenced other designers of the period. This intersection of sustainability and luxury demonstrates that upcycling has long been a part of even the most refined aspects of human creativity, seamlessly blending resourcefulness with artistry.

Quilting in Early America

Quilting in colonial America reflected the settlers' frugality and ingenuity. Imported fabrics were expensive, so women salvaged scraps, old clothing, and feed sacks to create quilts. These items provided warmth and functioned as decorative pieces in homes. Often made from small, irregular pieces of fabric, patchwork quilts were practical and economical. They symbolized resourcefulness, as every scrap of fabric was utilized.

Mass Production and Disposable Culture

The invention of factories made goods cheaper and more accessible, leading to the emergence of a "throwaway culture."

The availability of new materials like plastics discouraged repair and reuse.

Economic Pressures

During periods of economic hardship, such as the Great Depression (1930s), upcycling became a necessity for survival. Families repurposed materials to save money, such as transforming flour sacks into clothing.

War-Time Recycling and Upcycling

During World War I and II, governments encouraged citizens to recycle and upcycle for the war effort. Items like tin cans and rubber tires were repurposed for military use.

"Make Do and Mend" campaigns in the UK taught people how to repair and creatively reuse their belongings.

Post-War Era: The Rise of Consumerism and Counter Movements

After World War II, consumerism surged due to economic prosperity and technological advancements, pushing upcycling into the background. However, counter-cultural movements in the latter half of the 20th century revived the practice.

The Mid-Century Boom

The 1950s and 1960s were characterized by disposable goods and planned obsolescence, where products were designed to be replaced frequently.

Landfills expanded as waste accumulation became an environmental concern.

Environmental Awakening

The 1970s marked the birth of the modern environmental movement, with events like the first Earth Day (1970) highlighting the need for sustainable practices.

The publication of books like Silent Spring by Rachel Carson raised awareness about the ecological impact of waste.

Counter-Culture Movements

The hippie movement embraced upcycling as part of a broader rejection of consumerism. Clothing, furniture, and jewelry were often handmade from discarded materials.

Artists began incorporating upcycled materials into their works, paving the way for a connection between upcycling and creative expression.

Modern Upcycling: A Sustainability Revolution

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, upcycling evolved from a niche practice into a mainstream sustainability movement, driven by concerns about climate change, resource depletion, and waste management.

Coining the Term

The term "upcycling" was first popularized in the 1990s by Reiner Pilz, a German mechanical engineer, who contrasted it with traditional recycling. He emphasized upcycling's potential to enhance the value of materials, rather than degrading them as recycling often does.

Art and Design Movements

Designers like William McDonough and Michael Braungart advanced the concept of upcycling in their book Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things (2002), advocating for a circular economy where waste becomes a resource.

High-fashion brands began incorporating upcycled materials into their collections. For instance, Stella McCartney and Patagonia emphasized sustainable production and reuse.

Grassroots Initiatives

DIY enthusiasts and crafters used platforms like Etsy and Pinterest to share upcycling projects, fueling a global trend.

Community workshops and repair cafes encouraged people to upcycle everyday items, reducing waste at a local level.

Corporate Involvement

Businesses adopted upcycling as part of their corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives. For example, Adidas launched shoes made from ocean plastic.

The concept of "industrial symbiosis" emerged, where companies reused waste from one production process as input for another.

The Digital Age: Technology and Upcycling

The digital revolution has had a profound impact on upcycling, making it more accessible, innovative, and impactful.

Online Platforms

Social media platforms like Instagram popularized upcycling through viral projects and tutorials.

E-commerce sites specialized in upcycled goods, creating a marketplace for sustainable products.

Tech-Driven Solutions

3D printing enabled upcycling by turning waste materials into custom-designed objects.

Apps and online communities connected individuals with resources, tools, and ideas to start their own upcycling projects.

Challenges and Criticism

Despite its growing popularity, upcycling faces several challenges:

Scalability: Many upcycling projects are labor-intensive and not easily scalable.

Consumer Perception: Upcycled products are sometimes seen as less desirable or inferior compared to new items.

Material Limitations: Certain materials, like low-grade plastics, are difficult to upcycle effectively.

Cost and Accessibility: Upcycled goods can be more expensive than mass-produced alternatives, limiting their appeal to some consumers.

The Future of Upcycling

The future of upcycling looks promising as sustainability continues to dominate global conversations. Innovations in materials science, design, and policy could further embed upcycling into mainstream culture.

Emerging Trends

Circular economy initiatives are becoming more prevalent, promoting upcycling as a key strategy.

Innovations like biodegradable materials and regenerative design are expanding the possibilities for upcycling.

Global Collaboration

Governments, corporations, and communities are working together to promote upcycling through legislation, funding, and education.

Initiatives like the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s Circular Economy project aim to create systemic change.

Cultural Shifts

Younger generations are driving the upcycling movement, embracing it as a lifestyle choice aligned with environmental and ethical values.

Partnerships between artists, designers, and environmentalists continue to inspire new applications for upcycled materials.

Conclusion

The history of upcycling is a testament to human ingenuity and adaptability. What began as a necessity has evolved into a powerful tool for addressing the environmental challenges of our time. By embracing the principles of upcycling, we can create a more sustainable, creative, and resilient future. Whether through individual action, artistic expression, or corporate innovation, the potential of upcycling is limited only by our imagination.